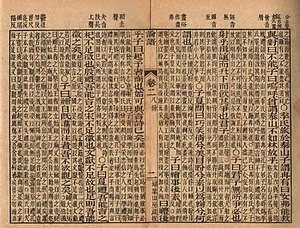

The Analects (Chinese: 論語; Old Chinese:*run ŋ(r)aʔ; pinyin: lúnyǔ; literally: "Edited Conversations"),[2] also known as the Analects of Confucius, is a collection of sayings and ideas attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled and written by Confucius' followers. It is believed to have been written during the Warring States period (475 BC–221 BC), and it achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). By the early Han dynasty the Analects was considered merely a "commentary" on the Five Classics, but the status of the Analects grew to be one of the central texts of Confucianism by the end of that dynasty.

The Analects (Chinese: 論語; Old Chinese:*run ŋ(r)aʔ; pinyin: lúnyǔ; literally: "Edited Conversations"),[2] also known as the Analects of Confucius, is a collection of sayings and ideas attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled and written by Confucius' followers. It is believed to have been written during the Warring States period (475 BC–221 BC), and it achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). By the early Han dynasty the Analects was considered merely a "commentary" on the Five Classics, but the status of the Analects grew to be one of the central texts of Confucianism by the end of that dynasty.

During the late Song dynasty (960-1279) the importance of the Analects as a philosophy work was raised above that of the older Five Classics, and it was recognized as one of the "Four Books". The Analects has been one of the most widely read and studied books in China for the last 2,000 years, and continues to have a substantial influence on Chinese and East Asian thought and values today. They were very important for Confucianism and China's overall morals.

Confucius believed that the welfare of a country depended on the moral cultivation of its people, beginning from the nation's leadership. He believed that individuals could begin to cultivate an all-encompassing sense of virtue through ren, and that the most basic step to cultivating ren was devotion to one's parents and older siblings. He taught that one's individual desires do not need to be suppressed, but that people should be educated to reconcile their desires via rituals and forms of propriety, through which people could demonstrate their respect for others and their responsible roles in society. He taught that a ruler's sense of virtue was his primary prerequisite for leadership. His primary goal in educating his students was to produce ethically well-cultivated men who would carry themselves with gravity, speak correctly, and demonstrate consummate integrity in all things.