Email Subscription

Subscribe via Email

Wednesday, May 31, 2017

300 BC-Callimachus

Callimachus (/kæˈlɪməkəs/; Greek: Καλλίμαχος, Kallimakhos; 310/305–240 BC[1]) was a native of the Greek colony of Cyrene, Libya.[2] He was a noted poet, critic and scholar at the Library of Alexandria and enjoyed the patronage of the Egyptian–Greek Pharaohs Ptolemy II Philadelphus[3] and Ptolemy III Euergetes. Although he was never made chief librarian, he was responsible for producing a bibliographic survey based upon the contents of the Library. This, his Pinakes, 120 volumes long,[4] provided the foundation for later work on the history of ancient Greek literature. As one of the earliest critic-poets, he typifies Hellenistic scholarship.

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

300 BC-Apollonius of Rhodes ---Argonautica

Apollonius of Rhodes (Ancient Greek: Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος Apollṓnios Rhódios; Latin: Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BCE), is best known as the author of the Argonautica, an epic poem about Jason and the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. The poem is one of the few extant examples of the epic genre and it was both innovative and influential, providing Ptolemaic Egypt with a "cultural mnemonic" or national "archive of images",[1] and offering the Latin poets Virgil and Gaius Valerius Flaccus a model for their own epics. His other poems, which survive only in small fragments, concerned the beginnings or foundations of cities, such as Alexandria and Cnidus – places of interest to the Ptolemies, whom he served as a scholar and librarian at the Library of Alexandria. A literary dispute with Callimachus, another Alexandrian librarian/poet, is a topic much discussed by modern scholars since it is thought to give some insight into their poetry, although there is very little evidence that there ever was such a dispute between the two men. In fact almost nothing at all is known about Apollonius and even his connection with Rhodes is a matter for speculation.[2] Once considered a mere imitator of Homer, and therefore a failure as a poet, his reputation has been enhanced by recent studies, with an emphasis on the special characteristics of Hellenistic poets as scholarly heirs of a long literary tradition writing at a unique time in history.[3]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Argonautica (Greek: Ἀργοναυτικά Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the Argonautica tells the myth of the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts to retrieve the Golden Fleece from remote Colchis. Their heroic adventures and Jason's relationship with the dangerous Colchian princess/sorceress Medea were already well known to Hellenistic audiences, which enabled Apollonius to go beyond a simple narrative, giving it a scholarly emphasis suitable to the times. It was the age of the great Library of Alexandria, and his epic incorporates his researches in geography, ethnography, comparative religion, and Homeric literature. However, his main contribution to the epic tradition lies in his development of the love between hero and heroine – he seems to have been the first narrative poet to study "the pathology of love".[3] His Argonautica had a profound impact on Latin poetry: it was translated by Varro Atacinus and imitated by Valerius Flaccus; it influenced Catullus and Ovid; and it provided Virgil with a model for his Roman epic, the Aeneid.[4]

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

300 BC-Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes (/ᵻˌkliːziˈæstiːz/; Greek: Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs, Hebrew: קֹהֶלֶת, qōheleṯ) is one of 24 books of the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible, where it is classified as one of the Ketuvim (or "Writings"). It is among the canonical Wisdom Books in the Old Testament of most denominations of Christianity. The title Ecclesiastes is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Kohelet (meaning "Gatherer", but traditionally translated as "Teacher" or "Preacher"[1]), the pseudonym used by the author of the book.

Ecclesiastes (/ᵻˌkliːziˈæstiːz/; Greek: Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs, Hebrew: קֹהֶלֶת, qōheleṯ) is one of 24 books of the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible, where it is classified as one of the Ketuvim (or "Writings"). It is among the canonical Wisdom Books in the Old Testament of most denominations of Christianity. The title Ecclesiastes is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Kohelet (meaning "Gatherer", but traditionally translated as "Teacher" or "Preacher"[1]), the pseudonym used by the author of the book.

The book dates from c.450–180 BC and is from the Middle Eastern tradition of the mythical autobiography, in which a character, describing himself as a king, relates his experiences and draws lessons from them, often self-critical. The author, introducing himself as "son of David, king in Jerusalem" (i.e., Solomon) discusses the meaning of life and the best way to live. He proclaims all the actions of man to be inherently hevel, meaning "vain" or "futile", ("mere breath"), as both wise and foolish end in death. Kohelet clearly endorses wisdom as a means for a well-lived earthly life. In light of this senselessness, one should enjoy the simple pleasures of daily life, such as eating, drinking, and taking enjoyment in one's work, which are gifts from the hand of God. The book concludes with the injunction: "Fear God, and keep his commandments; for that is the whole duty of everyone" (12:13).

Ecclesiastes has had a deep influence on Western literature. It contains several phrases that have resonated in British and American culture, and was quoted by Abraham Lincoln addressing Congress in 1862. American novelist Thomas Wolfe wrote: "[O]f all I have ever seen or learned, that book seems to me the noblest, the wisest, and the most powerful expression of man's life upon this earth—and also the highest flower of poetry, eloquence, and truth. I am not given to dogmatic judgments in the matter of literary creation, but if I had to make one I could say that Ecclesiastes is the greatest single piece of writing I have ever known, and the wisdom expressed in it the most lasting and profound."[2]

Monday, May 22, 2017

300 BC-Tolkāppiyam

The Tolkāppiyam (Tamil: தொல்காப்பியம்) is a work on the grammar of the Tamil language and the earliest extant work of Tamil literature[1] and linguistics. It is written in the form of noorpaa or short formulaic compositions and comprises three books – the Ezhuttadikaram, the Solladikaram and the Poruladikaram. Each of these books is further divided into nine chapters each. While the exact date of the work is not known, based on linguistic and other evidence, it has been dated variously between the third century BCE and the 10th century CE. Some modern scholars prefer to date it not as a single entity but in parts or layers.[2] There is also no firm evidence to assign the authorship of this treatise to any one author.

Tolkappiyam deals with orthography, phonology, morphology, semantics, prosody and the subject matter of literature. The Tolkāppiyam classifies the Tamil language into sentamil and koduntamil. The former refers to the classical Tamil used almost exclusively in literary works and the latter refers to the dialectal Tamil, spoken by the people in the various regions of ancient Tamilagam.[3]

Tolkappiyam categorises alphabet into consonants and vowels by analysing the syllables. It grammatises the use of words and syntaxes and moves into higher modes of language analysis. The Tolkāppiyam formulated thirty phonemes and three dependent sounds for Tamil.

Sunday, May 21, 2017

300 BC-300 AD- Sangam literature

The Sangam literature (Tamil: சங்க இலக்கியம், Canka ilakkiyam) is the ancient Tamil literature of the period in the history of ancient southern India (known as the Tamilakam) spanning from c. 300 BCE to 300 CE.[1][2][3][4][5]This collection contains 2381 poems in Tamil composed by 473 poets, some 102 of whom remain anonymous.[6]Most of the available Sangam literature are from the Third Sangam,[7] this period is known as the Sangam period, which referring to the prevalent Sangam legends claiming literary academies lasting thousands of years, giving the name to the corpus of literature.[8][9][10] Sangam literature is primarily secular, dealing with everyday themes in a Tamilakam context.[11]

The Sangam literature (Tamil: சங்க இலக்கியம், Canka ilakkiyam) is the ancient Tamil literature of the period in the history of ancient southern India (known as the Tamilakam) spanning from c. 300 BCE to 300 CE.[1][2][3][4][5]This collection contains 2381 poems in Tamil composed by 473 poets, some 102 of whom remain anonymous.[6]Most of the available Sangam literature are from the Third Sangam,[7] this period is known as the Sangam period, which referring to the prevalent Sangam legends claiming literary academies lasting thousands of years, giving the name to the corpus of literature.[8][9][10] Sangam literature is primarily secular, dealing with everyday themes in a Tamilakam context.[11]

The poems belonging to Sangam literature were composed by Tamil poets, both men and women, from various professions and classes of society. These poems were later collected into various anthologies, edited, and with colophons added by anthologists and annotators around 1000 AD. Sangam literature fell out of popular memory soon thereafter, until they were rediscovered in the 19th century by scholars such as Arumuga Navalar, C. W. Thamotharampillai and U. V. Swaminatha Iyer.

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

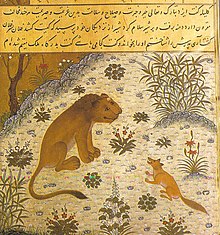

300 BC-Vishnu Sharma and Panchatantra

Vishnu Sharma (Sanskrit: विष्णुशर्मन् / विष्णुशर्मा) was an Indian scholar and author who is believed to have written the Panchatantra collection of fables.[1] The exact period of the composition of the Panchatantra is uncertain, and estimates vary from 1200 BCE to 300 CE.[1] Some scholars place him in the 3rd century BCE.[2]

Vishnu Sharma (Sanskrit: विष्णुशर्मन् / विष्णुशर्मा) was an Indian scholar and author who is believed to have written the Panchatantra collection of fables.[1] The exact period of the composition of the Panchatantra is uncertain, and estimates vary from 1200 BCE to 300 CE.[1] Some scholars place him in the 3rd century BCE.[2]

Panchatantra is one of the most widely translated non-religious books in history. The Panchatantra was translated into Middle Persian/Pahlavi in 570 CE by Borzūya and into Arabic in 750 CE by Persian scholar Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa as Kalīlah wa Dimnah (Arabic: كليلة و دمنة).[3][4] In Baghdad, the translation commissioned by Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, is claimed to have become "second only to the Qu'ran in popularity."[5] "As early as the eleventh century this work reached Europe, and before 1600 it existed in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech, and perhaps other Slavonic languages. Its range has extended from Java to Iceland."[6] In France, "at least eleven Panchatantra tales are included in the work of Jean de La Fontaine."[5]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Panchatantra (IAST: Pañcatantra, Sanskrit: पञ्चतन्त्र, 'Five Devices') is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in verse and prose, arranged within a frame story. The original Sanskrit work, which some scholars believe was composed around the 3rd century BCE,[1] is attributed to Vishnu Sharma. It is based on older oral traditions, including "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".[2]

It is "certainly the most frequently translated literary product of India",[3] and these stories are among the most widely known in the world.[4] To quote Edgerton (1924):[5]

...there are recorded over two hundred different versions known to exist in more than fifty languages, and three-quarters of these languages are extra-Indian. As early as the eleventh century this work reached Europe, and before 1600 it existed in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech, and perhaps other Slavonic languages. Its range has extended from Java to Iceland... [In India,] it has been worked over and over again, expanded, abstracted, turned into verse, retold in prose, translated into medieval and modern vernaculars, and retranslated into Sanskrit. And most of the stories contained in it have "gone down" into the folklore of the story-loving Hindus, whence they reappear in the collections of oral tales gathered by modern students of folk-stories.

Thus it goes by many names in many cultures. In India, it had at least 25 recensions, including the Sanskrit Tantrākhyāyikā[6] (Sanskrit: तन्त्राख्यायिका) and inspired the Hitopadesha. It was translated into Middle Persian in 570 CE by Borzūya. This became the basis for a Syriac translation as Kalilag and Damnag[7] and a translation into Arabic in 750 CE by Persian scholar Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa as Kalīlah wa Dimnah[8] (Arabic: كليلة ودمنة). A New Persian version by Rudaki in the 12th century became known as Kalīleh o Demneh[9] (Persian: کلیله و دمنه) and this was the basis of Kashefi's 15th century Anvār-i Suhaylī or Anvār-e Soheylī[10] (Persian: انوار سهیلی, 'The Lights of Canopus'). The book in different form is also known as The Fables of Bidpai[11][12] (or Pilpai, in various European languages) or The Morall Philosophie of Doni (English, 1570).

Monday, May 15, 2017

300 BC-Liber Linteus

The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis (Latin for "Linen Book of Zagreb", also rarely known as Liber Agramensis, "Book of Agram") is the longest Etruscan text and the only extant linen book, dated to the 3rd century BCE. It remains mostly untranslated because of the lack of knowledge about the Etruscan language, though the few words which can be understood indicate that the text is most likely a ritual calendar.

The fabric of the book was preserved when it was used for mummy wrappings in Ptolemaic Egypt. The mummy was bought in Alexandria in 1848 and since 1867 both the mummy and the manuscript have been kept in Zagreb, Croatia, now in a refrigerated room at the Archaeological Museum.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

300 BC-Avesta

The Avesta /əˈvɛstə/ is the primary collection of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, composed in the otherwise unrecorded Avestan language.[1]

The Avesta /əˈvɛstə/ is the primary collection of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, composed in the otherwise unrecorded Avestan language.[1]

The Avesta texts fall into several different categories, arranged either by dialect, or by usage. The principal text in the liturgical group is the Yasna, which takes its name from the Yasna ceremony, Zoroastrianism's primary act of worship, and at which the Yasna text is recited. The most important portion of the Yasna texts are the five Gathas, consisting of seventeen hymns attributed to Zoroaster himself. These hymns, together with five other short Old Avestan texts that are also part of the Yasna, are in the Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan language. The remainder of the Yasna's texts are in Younger Avestan, which is not only from a later stage of the language, but also from a different geographic region.

Extensions to the Yasna ceremony include the texts of the Vendidad and the Visperad.[2] The Visperad extensions consist mainly of additional invocations of the divinities (yazatas),[3] while the Vendidad is a mixed collection of prose texts mostly dealing with purity laws.[3] Even today, the Vendidad is the only liturgical text that is not recited entirely from memory.[3] Some of the materials of the extended Yasna are from the Yashts, [3] which are hymns to the individual yazatas. Unlike the Yasna, Visperad and Vendidad, the Yashts and the other lesser texts of the Avesta are no longer used liturgically in high rituals. Aside from the Yashts, these other lesser texts include the Nyayesh texts, the Gah texts, the Siroza, and various other fragments. Together, these lesser texts are conventionally called Khordeh Avesta or "Little Avesta" texts. When the first Khordeh Avesta editions were printed in the 19th century, these texts (together with some non-Avestan language prayers) became a book of common prayer for lay people.[2]

The term Avesta is from the 9th/10th-century works of Zoroastrian tradition in which the word appears as Zoroastrian Middle Persian abestāg, Book Pahlavi ʾp(y)stʾkʼ. In that context, abestāg texts are portrayed as received knowledge, and are distinguished from the exegetical commentaries (the zand) thereof. The literal meaning of the word abestāg is uncertain; it is generally acknowledged to be a learned borrowing from Avestan, but none of the suggested etymologies have been universally accepted.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

300 BC-Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Venerable Mahindra

Theravada Buddhism is the religion of 70.1% of the population of Sri Lanka.[3] The island has been a center of Buddhist scholarship and learning since the introduction of Buddhism in the third century BCE producing eminent scholars such as Buddhaghosa and preserving the vast Pāli Canon. Throughout most of its history, Sinhalese kings have played a major role in the maintenance and revival of the Buddhist institutions of the island. During the 19th century, a modern Buddhist revival took place on the island which promoted Buddhist education and learning. There are around 6,000 Buddhist monasteries on Sri Lanka with approximately 15,000 monks.[4]

Theravada Buddhism is the religion of 70.1% of the population of Sri Lanka.[3] The island has been a center of Buddhist scholarship and learning since the introduction of Buddhism in the third century BCE producing eminent scholars such as Buddhaghosa and preserving the vast Pāli Canon. Throughout most of its history, Sinhalese kings have played a major role in the maintenance and revival of the Buddhist institutions of the island. During the 19th century, a modern Buddhist revival took place on the island which promoted Buddhist education and learning. There are around 6,000 Buddhist monasteries on Sri Lanka with approximately 15,000 monks.[4]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mahinda (Sanskrit Mahendra; born third century BCE in Ujjain, modern Madhya Pradesh, India) was a Buddhist monk depicted in Buddhist sources as bringing Buddhism to Sri Lanka.[1] He was the first-born son of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka from his wife Devi and the elder brother of Sanghamitra.

Mahinda (Sanskrit Mahendra; born third century BCE in Ujjain, modern Madhya Pradesh, India) was a Buddhist monk depicted in Buddhist sources as bringing Buddhism to Sri Lanka.[1] He was the first-born son of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka from his wife Devi and the elder brother of Sanghamitra.

Ashoka named him Mahendra, meaning "conqueror of the world". But Mahendra, inspired by his mother, became a Buddhist monk.

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

399 BC-Socrates is tried for impiety

The trial of Socrates (399 BC) was held to determine the philosopher’s guilt of two charges: asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: “failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges” and “introducing new deities”.

The death sentence of Socrates was the legal consequence of asking politico-philosophic questions of his students, from which resulted the two accusations of moral corruption and of impiety. At trial, the majority of the dikasts (male-citizen jurors chosen by lot) voted to convict him of the two charges; then, consistent with common legal practice, voted to determine his punishment, and agreed to a sentence of death to be executed by Socrates’s drinking a poisonous beverage of hemlock.

Primary-source accounts of the trial and execution of Socrates are the Apology of Socrates by Plato and the Apology of Socrates to the Jury by Xenophon of Athens, who had been his student; contemporary interpretations include The Trial of Socrates (1988) by the journalist I. F. Stone, and Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths (2009) by the Classics scholar Robin Waterfield.[1]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)