Vishnu Sharma (Sanskrit: विष्णुशर्मन् / विष्णुशर्मा) was an Indian scholar and author who is believed to have written the Panchatantra collection of fables.[1] The exact period of the composition of the Panchatantra is uncertain, and estimates vary from 1200 BCE to 300 CE.[1] Some scholars place him in the 3rd century BCE.[2]

Vishnu Sharma (Sanskrit: विष्णुशर्मन् / विष्णुशर्मा) was an Indian scholar and author who is believed to have written the Panchatantra collection of fables.[1] The exact period of the composition of the Panchatantra is uncertain, and estimates vary from 1200 BCE to 300 CE.[1] Some scholars place him in the 3rd century BCE.[2]

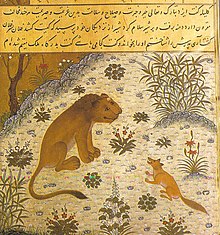

Panchatantra is one of the most widely translated non-religious books in history. The Panchatantra was translated into Middle Persian/Pahlavi in 570 CE by Borzūya and into Arabic in 750 CE by Persian scholar Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa as Kalīlah wa Dimnah (Arabic: كليلة و دمنة).[3][4] In Baghdad, the translation commissioned by Al-Mansur, the second Abbasid Caliph, is claimed to have become "second only to the Qu'ran in popularity."[5] "As early as the eleventh century this work reached Europe, and before 1600 it existed in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech, and perhaps other Slavonic languages. Its range has extended from Java to Iceland."[6] In France, "at least eleven Panchatantra tales are included in the work of Jean de La Fontaine."[5]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Panchatantra (IAST: Pañcatantra, Sanskrit: पञ्चतन्त्र, 'Five Devices') is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in verse and prose, arranged within a frame story. The original Sanskrit work, which some scholars believe was composed around the 3rd century BCE,[1] is attributed to Vishnu Sharma. It is based on older oral traditions, including "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".[2]

It is "certainly the most frequently translated literary product of India",[3] and these stories are among the most widely known in the world.[4] To quote Edgerton (1924):[5]

Thus it goes by many names in many cultures. In India, it had at least 25 recensions, including the Sanskrit Tantrākhyāyikā[6] (Sanskrit: तन्त्राख्यायिका) and inspired the Hitopadesha. It was translated into Middle Persian in 570 CE by Borzūya. This became the basis for a Syriac translation as Kalilag and Damnag[7] and a translation into Arabic in 750 CE by Persian scholar Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa as Kalīlah wa Dimnah[8] (Arabic: كليلة ودمنة). A New Persian version by Rudaki in the 12th century became known as Kalīleh o Demneh[9] (Persian: کلیله و دمنه) and this was the basis of Kashefi's 15th century Anvār-i Suhaylī or Anvār-e Soheylī[10] (Persian: انوار سهیلی, 'The Lights of Canopus'). The book in different form is also known as The Fables of Bidpai[11][12] (or Pilpai, in various European languages) or The Morall Philosophie of Doni (English, 1570).

No comments:

Post a Comment