Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism,

[n 1] or more natively

Mazdayasna,

[1] is one of the world's oldest extant religions, "combining a

cosmogonic dualism and

eschatological monotheism in a manner unique [...] among the major religions of the world".

[2] Ascribed to the teachings of the Iranian prophet

Zoroaster (or Zarathustra),

[3] it exalts a deity of wisdom,

Ahura Mazda (

Wise Lord), as its

Supreme Being.

[4] Major features of Zoroastrianism, such as

messianism,

heaven and

hell, and

free will have, some believe, influenced other religious systems, including

Second Temple Judaism,

Gnosticism,

Christianity, and

Islam.

[5] With possible roots dating back to the

second millennium BCE, Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the

5th-century BCE,

[4] and along with a

Mithraic Median prototype and a

Zurvanist Sassanid successor it served as the

state religion of the

pre-Islamic Iranian empires from around 600 BCE to 650 CE. Zoroastrianism was

suppressed from the 7th century onwards following the

Muslim conquest of Persia of 633-654.

[6] Recent estimates place the current number of Zoroastrians at around 2.6 million, with most living in

India and in

Iran.

[7][8][better source needed][n 2] Besides the Zoroastrian diaspora, the older Mithraic faith

Yazdânism is still practised amongst

Kurds.

[n 3]

The religious philosophy of

Zoroaster divided the early Iranian gods of Proto-Indo-Iranian tradition.

[9] The most important texts of the religion are those of the

Avesta,

[10] the Zoroastrians' holy book. In Zoroastrianism, the

creator Ahura Mazda, through the

Spenta Mainyu (Good Spirit, "Bounteous Immortals")

[11] is an all-good "father" of

Asha (Truth, "order, justice"),

[12][13] in opposition to

Druj ("falsehood, deceit")

[14][15] and no

evil originates from "him".

[16] "He" and his works are evident to humanity through the six primary

Amesha Spentas[17] and the host of other

Yazatas, through whom worship of Mazda is ultimately directed. Spenta Mainyu adjoined unto "truth"

[18] oppose the Spirit's opposite,

[19][20] Angra Mainyu and its forces born of Akəm Manah (“evil thinking”).

[21]

Zoroastrianism has no major theological divisions, though it is not uniform; modern-era influences having a significant impact on individual and local beliefs, practices, values and vocabulary, sometimes merging with tradition and in other cases displacing it.

[22] In Zoroastrianism, the purpose in

life is to "be among those who renew the world...to make the world progress towards perfection". Its basic maxims include:

- Humata, Hukhta, Huvarshta, which mean: Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds.

- There is only one path and that is the path of Truth.

- Do the right thing because it is the right thing to do, and then all beneficial rewards will come to you also.

The most important texts of the religion are those of the

Avesta, which includes the writings of Zoroaster known as the

Gathas, enigmatic poems that define the religion's precepts, and the

Yasna, the scripture. The full name by which Zoroaster addressed the deity is: Ahura, The Lord Creator, and Mazda, Supremely Wise. He proclaimed that there is only one God, the singularly creative and sustaining force of the Universe. He also stated that human beings are given a right of choice, and because of cause and effect are also responsible for the consequences of their choices. Zoroaster's teachings focused on

responsibility, and did not introduce a

devil per se. The contesting force to Ahura Mazda was called Angra Mainyu, or angry spirit. Post-Zoroastrian scripture introduced the concept of Ahriman, the Devil, which was effectively a personification of Angra Mainyu.

[23]

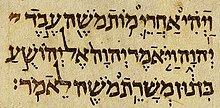

Yasna 28.1 (Bodleian MS J2)

- Primary religious texts, that is, the Avesta collection:

- The Yasna, the primary liturgical collection, includes the Gathas.

- The Visperad, a collection of supplements to the Yasna.

- The Yashts, hymns in honor of the divinities.

- The Vendidad, describes the various forms of evil spirits and ways to confound them.

- shorter texts and prayers, the Yashts the five Nyaishes ("worship, praise"), the Sirozeh and the Afringans (blessings).

- There are some 60 secondary religious texts, none of which are considered scripture. The most important of these are:

- The Denkard (middle Persian, 'Acts of Religion'),

- The Bundahishn, (middle Persian, 'Primordial Creation')

- The Menog-i Khrad, (middle Persian, 'Spirit of Wisdom')

- The Arda Viraf Namak (middle Persian, 'The Book of Arda Viraf')

- The Sad-dar (modern Persian, 'Hundred Doors', or 'Hundred Chapters')

- The Rivayats, 15th-18th century correspondence on religious issues

- For general use by the laity:

- The Zend (lit. commentaries), various commentaries on and translations of the Avesta.

- The Khordeh Avesta, Zoroastrian prayer book for lay people from the Avesta.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Dēnkard[pronunciation?] or Dēnkart (Middle Persian: "Acts of Religion") is a 10th-century compendium of the Mazdaen Zoroastrian beliefs and customs. The Denkard is to a great extent an "Encyclopedia of Mazdaism"[1] and is a most valuable source of information on the religion. The Denkard is not itself considered scripture.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Although the Bundahishn draws on the

Avesta and develops ideas alluded to in those texts, it is not itself scripture. The content reflects Zoroastrian scripture, which in turn reflects both ancient Zoroastrian and pre-Zoroastrian beliefs. In some cases, the text alludes to contingencies of post-7th century

Islamic Iran, and yet in other cases (e.g. in the idea that the moon is further away than the stars) reiterates scripture even though science had by then determined otherwise.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Also transcribed as

Menog-i Xrad from

Pahlavi, or from

Pazand Minuy-e X(e/a)rad and transcribed from

modern Persian [Minuj-e Xeræd], (meaning: "Spirit of Wisdom") the text is a Zoroastrian Pahlavi book in sixty-three chapters (a preamble and sixty-two questions and answers), in which a symbolic character called Dānāg (lit., “knowing, wise”) poses questions to the personified

Spirit of Wisdom (Mēnōg ī xrad), who is extolled in the preamble and identified in two places (2.95, 57.4) with innate wisdom (āsn xrad). The book, like most Pahlavi books, is based on oral tradition and has no known author. According to the preamble, Dānāg, searching for truth, traveled to many countries, associated himself with many savants, and learned about various opinions and beliefs. When he discovered the virtue of xrad (1.51) the Spirit of Wisdom appeared to him to answer his questions.

[1]

The book belongs to the genre of andarz (advices) literature, containing mostly practical wisdom on the benefits of drinking wine moderately and the harmful effects of overindulging in it (20, 33, 39, 50, 51, 54, 55, 59, 60), although advice on religious questions is by no means lacking. For example, there are passages on keeping quiet while eating (2.33-34); on not walking without wearing the sacred girdle (kostī) and undershirt (sodra; 2.35-36); on not walking with only one shoe on (2.37-38); on not urinating in a standing position (2.39-40); on gāhānbār and hamāg-dēn ceremonies (4.5); on libation (zōhr) and the yasna ceremony (yazišn; 5.13); on not burying the dead (6.9); on marriage with next of kin (xwēdōdah) and trusteeship (stūrīh; 36); on belief in dualism (42); on praying three times a day and repentance before the sun, the moon, and fire (53); on belief in Ohrmazd as the creator and in the destructiveness of Ahreman and belief in *stōš (the fourth morning after death), resurrection, and the Final Body (tan ī pasēn; 63). The first chapter, which is also the longest (110 pars.), deals in detail with the question of what happens to people after death and the separation of soul from body.

[1]

It is believed by some scholars that this text has been first written in Pazand and latter, using the Pazand text it was re-written in Pahlavi but others believe that this text was originally written in Pahlavi and later written in Pazand,

Sanskrit,

Gujarati and

Persian. The oldest surviving manuscripts there are L19, found in the

British Library, written in Pazand and Gujarati which is believed to date back to 1520 AD. One of the characteristics of L19 text is that the word

Xrad (wisdom) is spelled as

Xard throughout the text. the oldest surviving Pahlavi version of this text is K43 found in

Copenhagen's Royal Library,

Denmark.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Book of Arda Viraf[pronunciation?] is a Zoroastrian religious text of the Sassanid era, written in the Middle Persian language. It contains about 8,800 words.[1] It describes the dream-journey of a devout Zoroastrian (the 'Viraf' of the story) through the next world. The text assumed its definitive form in the 9th-10th centuries C.E., after a long series of emendations.[2]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sanskrit cognate is

Shat-Dwar (Shat=Hundred, Dwar=Door)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Zend or

Zand is a

Zoroastrian technical term for

exegetical glosses, paraphrases, commentaries and translations of the

Avesta's texts. The term

zand is a contraction of the

Avestan language word

zainti, meaning "interpretation", or "as understood".

Zand glosses and commentaries exist in several languages, including in the Avestan language itself. These Avestan language exegeses sometimes accompany the original text being commented upon, but are more often elsewhere in the canon. An example of exegesis in the Avestan language itself includes

Yasna 19-21, which is a set of three Younger Avestan commentaries on the three Gathic Avestan 'high prayers' of

Yasna 27.

Zand also appear to have once existed in a variety of

Middle Iranian languages, but of these Middle Iranian commentaries, the

Middle Persian zand is the only to survive fully, and is for this reason regarded as 'the'

zand.

With the notable exception of the

Yashts, almost all surviving Avestan texts have their Middle Persian

zand, which in some manuscripts appear alongside (or interleaved with) the text being glossed. The practice of including non-Avestan commentaries alongside the Avestan texts led to two different misinterpretations in western scholarship of the term

zand; these misunderstandings are described

below. These glosses and commentaries were not intended for use as theological texts by themselves but for religious instruction of the (by then) non-Avestan-speaking public. In contrast, the Avestan language texts remained sacrosanct and continued to be recited in the Avestan language, which was considered a

sacred language. The Middle Persian

zand can be subdivided into two subgroups, those of the surviving Avestan texts, and those of the lost Avestan texts.

A consistent exegetical procedure is evident in manuscripts in which the original Avestan and its zand coexist. The priestly scholars first translated the Avestan as literally as possible. In a second step, the priests then translated the Avestan idiomatically. In the final step, the idiomatic translation was complemented with explanations and commentaries, often of significant length, and occasionally with different authorities being cited.

Several important works in Middle Persian contain selections from the

zand of Avestan texts, also of Avestan texts which have since been lost. Through comparison of selections from lost texts and from surviving texts, it has been possible to distinguish between the translations of Avestan works and the commentaries on them, and thus to some degree reconstruct the content of some of the lost texts. Among those texts is the

Bundahishn, which has

Zand-Agahih ("Knowledge from the

Zand") as its subtitle and is crucial to the understanding of Zoroastrian cosmogony and eschatology. Another text, the

Wizidagiha, "Selections (from the Zand)", by the 9th century priest Zadspram, is a key text for understanding Sassanid-era Zoroastrian orthodoxy. The

Denkard, a 9th or 10th century text, includes extensive summaries and quotations of

zand texts.

The priests' practice of including commentaries alongside the text being commented upon led to two different misunderstandings in 18th/19th century western scholarship:

- The incorrect treatment of "Zend" and "Avesta" as synonyms and the mistaken use of "Zend-Avesta" as the name of Zoroastrian scripture. This mistake derives from a misunderstanding of the distinctions made by priests between manuscripts for scholastic use ("Avesta-with-Zand"), and manuscripts for liturgical use ("clean"). In western scholarship, the former class of manuscripts was misunderstood to be the proper name of the texts, hence the misnomer "Zend-Avesta" for the Avesta. In priestly use however, "Zand-i-Avesta" or "Avesta-o-Zand" merely identified manuscripts that are not suitable for ritual use since they are not "clean" (sade) of non-Avestan elements.

- The mistaken use of Zend as the name of a language or script. In 1759, Anquetil-Duperron reported having been told that Zend was the name of the language of the more ancient writings. Similarly, in his third discourse, published in 1798, Sir William Jones recalls a conversation with a Hindu priest who told him that the script was called Zend, and the language Avesta. This mistake results from a misunderstanding of the term pazend, which actually denotes the use of the Avestan alphabet for writing certain Middle Persian texts. Rasmus Rask's seminal work, A Dissertation on the Authenticity of the Zend Language (Bombay, 1821), may have contributed to the confusion.

Propagated by N. L. Westergaard's Zendavesta, or the religious books of the Zoroastrians (Copenhagen, 1852–54), by the early/mid 19th century, the confusion became too universal in Western scholarship to be easily reversed, and Zend-Avesta, although a misnomer, continued to be fashionable well into the 20th century.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Khordeh Avesta, meaning 'little, or lesser, or small Avesta', is the name given to two different collections of

Zoroastrian religious texts. One of the two collections includes the other and takes its name from it.

- In a narrow sense, the term applies to a particular manuscript tradition that includes only the five Nyayesh texts, the five Gah texts, the four Afrinagans, and five introductory chapters that consist of quotations from various passages of the Yasna.[1] More generally, the term may also be applied to Avestan texts other than the lengthy liturgical Yasna, Visperad and Vendidad. The term then also extends to the twenty-one yashts and the thirty Siroza texts, but does not usually encompass the various Avestan language fragments found in other works.

- In the 19th century, when the first Khordeh Avesta editions were printed, the selection of Avesta texts described above (together with some non-Avestan language prayers) became a book of common prayer for lay people.[2] In addition to the texts mentioned above, the published Khordeh Avesta editions also included selections from the Yasna necessary for daily worship, such as the Ahuna Vairya and Ashem Vohu. The selection of texts is not fixed, and so publishers are free to include any text they choose. Several Khordeh Avesta editions are quite comprehensive, and include Pazend prayers, modern devotional compositions such as the poetical or semi-poetical Gujarati monagats, or glossaries and other reference lists such as dates of religious events.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Yasna is the

Avestan language name of

Zoroastrianism's principal act of worship, and it is also the name of the primary liturgical collection of

Avesta texts, recited during that

yasna ceremony.

The function of the

yasna ceremony is, very roughly described, to strengthen the orderly spiritual and material creations of

Ahura Mazda against the assault of the destructive forces of

Angra Mainyu. The

yasna service, that is, the recitation of the Yasna texts, culminates in the

apæ zaothra, the "offering to the waters." The ceremony may also be extended by recitation of the

Visperad and

Vendidad texts. A normal

yasna ceremony, without extensions, takes about two hours when it is recited by an experienced priest.

The

Yasna texts constitute 72 chapters altogether, composed at different times and by different authors. The middle chapters include of the (linguistically) oldest texts of the Zoroastrian canon. These very ancient texts, in the very archaic and linguistically difficult

Old Avestan language, include the four most sacred Zoroastrian prayers, and also 17 chapters comprising the five

Gathas, hymns that are considered to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. Several sections of the

Yasna include

exegetical comments.

Yasna chapter and verse pointers are traditionally abbreviated with

Y.

The Avestan language word

yasna literally means 'oblation' or 'worship'. The word is linguistically (but not functionally) equivalent to

Vedic Yajna. Unlike Vedic

Yajna, Zoroastrian

Yasna has "to do with water rather than fire."

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Visperad[pronunciation?] or

Visprad is either a particular

Zoroastrian religious ceremony or the name given to a passage collection within the greater

Avesta compendium of texts.

The Visperad ceremony "consists of the rituals of the

Yasna, virtually unchanged, but with a

liturgy extended by twenty-three

[a] supplementary sections."

[1] These supplementary sections (

kardag) are then – from a philological perspective – the passages that make up the Visperad collection. The standard abbreviation for

Visperad chapter-verse pointers is

Vr., though

Vsp. may also appear in older sources.

The name

Visperad is a contraction of

Avestan vispe ratavo,

[b] with an ambiguous meaning. Subject to how

ratu is translated,

[c] vispe ratavo may be translated as "(prayer to) all patrons"

[2] or "all masters"

[1] or the older and today less common "all chiefs."

[3] or "all lords."

The Visperad ceremony – in medieval Zoroastrian texts referred to as the

Jesht-i Visperad,

[4] that is, "Worship through praise (Yasht) of all the patrons," – developed

[d] as an "extended service" for celebrating the

gahambars,

[4] the high

Zoroastrian festivals that celebrate six season(al) events. As seasonal ("year cycle") festivals, the

gahambars are dedicated to the

Amesha Spentas, the divinites that are in tradition identified with specific aspects of creation, and through whom Ahura Mazda realized ("with his thought") creation. These "bounteous immortals" (

amesha spentas) are the "all patrons" – the

vispe ratavo – who apportion the bounty of creation. However, the Visperad ceremony itself is dedicated to

Ahura Mazda, the

ratūm berezem "high Master."

[4]

The

Visperad collection has no unity of its own, and is never recited separately from the Yasna. During a recital of the Visperad ceremony, the

Visperad sections are not recited

en bloc but are instead interleaved into the Yasna recital.

[5] The

Visperad itself exalts several texts of the

Yasna collection, including the

Ahuna Vairya and the

Airyaman ishya, the

Gathas, and the

Yasna Haptanghaiti (

Visperad 13-16, 18-21, 23-24

[6]) Unlike in a regular

Yasna recital, the

Yasna Haptanghaiti is recited a second time between the 4th and 5th Gatha (the first time between the 1st and 2nd as in a standard

Yasna). This second recitation is performed by the assistant priest (the

raspi), and is often slower and more melodious.

[5] In contrast to

barsom bundle of a regular Yasna, which has 21 rods (

tae), the one used in a Visperad service has 35 rods.

The Visperad is only performed in the

Havan Gah – between sunrise and noon – on the six

gahambar days.

[4]

Amongst Iranian Zoroastrians, for whom the seasonal festivals have a greater significance than for their Indian co-religionists

[citation needed], the Visperad ceremony has undergone significant modifications in the 20th century.

[7] The ritual – which is technically an "inner" one requiring

ritual purity – is instead celebrated as an "outer" ritual where ritual purity is not a requirement. Often there is only one priest instead of the two that are actually required, and the priests sit at a table with only a lamp or candle representing the fire, so avoiding accusations of "fire worship."

[e][8]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The

Yashts (

Yašts) are a collection of twenty-one hymns in the

Younger Avestan language. Each of these hymns invokes a specific

Zoroastrian divinity or concept.

Yasht chapter and verse pointers are traditionally abbreviated as

Yt.

The word

yasht derives from Avestan

yešti, "for venerate" (see

Christian Bartholomae`s Altiranisches wörterbuch, section 1298), and several hymns of the

Yasna liturgy that "venerate by praise" are—in tradition—also nominally called

yashts. These "hidden" Yashts are: the

Barsom Yasht (

Yasna 2), another

Hom Yasht in

Yasna 9-11, the

Bhagan Yasht of

Yasna 19-21, a hymn to

Ashi in

Yasna 52, another

Sarosh Yasht in

Yasna 57, the praise of the (hypostasis of) "prayer" in

Yasna 58, and a hymn to the

Ahurani in

Yasna 68. Since these are a part of the primary litury, they do not count among the twenty-one hymns of the

Yasht collection.

All the hymns of the

Yasht collection "are written in what appears to be prose, but which, for a large part, may originally have been a (basically) eight-syllable verse, oscillating between four and thirteen syllables, and most often between seven and nine."

[1]

The twenty-one yashts of the collection (notes follow):

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Vendidad[pronunciation?] or Videvdat is a collection of texts within the greater compendium of the Avesta. However, unlike the other texts of the Avesta, the Vendidad is an ecclesiastical code, not a liturgical manual.

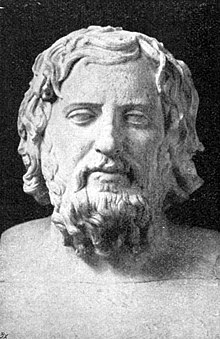

Xenophon of Athens (/ˈzɛnəfən, -ˌfɒn/; Greek: Ξενοφῶν Greek pronunciation: [ksenopʰɔ̂ːn], Xenophōn; c. 430–354 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher, historian, soldier and mercenary, and a student of Socrates.[1] As a historian, Xenophon is known for recording the history of his contemporary time, the late-5th and early-4th centuries BC, such as the Hellenica, about the final seven years and the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC); as such, the Hellenica is a thematic continuation of the History of the Peloponnesian War, by Thucydides. As a mercenary soldier of the Ten Thousand, he participated in the failed campaign of Cyrus the Younger, to claim the Persian throne from his brother Artaxerxes II of Persia, and recounts the events in Anabasis (An Ascent), his most notable history.

Xenophon of Athens (/ˈzɛnəfən, -ˌfɒn/; Greek: Ξενοφῶν Greek pronunciation: [ksenopʰɔ̂ːn], Xenophōn; c. 430–354 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher, historian, soldier and mercenary, and a student of Socrates.[1] As a historian, Xenophon is known for recording the history of his contemporary time, the late-5th and early-4th centuries BC, such as the Hellenica, about the final seven years and the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC); as such, the Hellenica is a thematic continuation of the History of the Peloponnesian War, by Thucydides. As a mercenary soldier of the Ten Thousand, he participated in the failed campaign of Cyrus the Younger, to claim the Persian throne from his brother Artaxerxes II of Persia, and recounts the events in Anabasis (An Ascent), his most notable history.