Pausanias

Pausanias (

;

Greek:

Παυσανίας Pausanías; c. AD 110 – c. 180)

[1] was a

Greek traveler and

geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the time of Roman emperors

Hadrian,

Antoninus Pius and

Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his

Description of Greece (

Ἑλλάδος περιήγησις Hellados Periegesis),

[2] a lengthy work that describes

ancient Greece from his first-hand observations. This work provides crucial information for making links between classical literature and modern

archaeology. Andrew Stewart assesses him as:

A careful, pedestrian writer...interested not only in the grandiose or the exquisite but in unusual sights and obscure ritual. He is occasionally careless or makes unwarranted inferences, and his guides or even his own notes sometimes mislead him, yet his honesty is unquestionable, and his value without par.

[3]

Pausanias was born in 110 AD into a

Greek family

[4] and was probably a native of

Lydia; he was certainly familiar with the western coast of

Asia Minor, but his travels extended far beyond the limits of

Ionia. Before visiting Greece, he had been to

Antioch,

Joppa and

Jerusalem, and to the banks of the

River Jordan. In

Egypt, he had seen the

pyramids, while at the temple of

Ammon, he had been shown the hymn once sent to that shrine by

Pindar. In

Macedonia, he appears to have seen the alleged tomb of

Orpheus in

Libethra (modern

Leivithra).

[5] Crossing over to

Italy, he had seen something of the cities of

Campania and of the wonders of

Rome. He was one of the first to write of seeing the ruins of

Troy,

Alexandria Troas, and Mycenae.

Pausanias'

Description of Greece is in ten books, each dedicated to some portion of Greece. He begins his tour in

Attica, where the city of Athens and its demes dominate the discussion. Subsequent books describe

Corinthia (2nd book),

Laconia (3rd),

Messenia (4th),

Elis (5th and 6th),

Achaea (7th),

Arcadia (8th),

Boetia (9th),

Phocis and

Ozolian Locris (10th). The project is more than topographical; it is a cultural geography. Pausanias digresses from the description of architectural and artistic objects to review the mythological and historical underpinnings of the society that produced them. As a Greek writing under the auspices of the Roman empire, he found himself in an awkward cultural space, between the glories of the Greek past he was so keen to describe and the realities of a Greece beholden to Rome as a dominating imperial force. His work bears the marks of his attempt to navigate that space and establish an identity for Roman Greece.

He is not a naturalist by any means, though he does from time to time comment on the physical realities of the Greek landscape. He notices the pine trees on the sandy coast of

Elis, the deer and the wild boars in the oak woods of

Phelloe, and the crows amid the giant oak trees of

Alalcomenae. It is mainly in the last section that Pausanias touches on the products of nature, such as the wild strawberries of

Helicon, the date palms of

Aulis, and the olive oil of

Tithorea, as well as the tortoises of Arcadia and the "white blackbirds" of

Cyllene.

Pausanias is most at home in describing the religious art and architecture of Olympia and of

Delphi. Yet, even in the most secluded regions of Greece, he is fascinated by all kinds of depictions of gods, holy relics, and many other sacred and mysterious objects. At

Thebes he views the shields of those who died at the

Battle of Leuctra, the ruins of the house of Pindar, and the statues of

Hesiod,

Arion,

Thamyris, and

Orpheus in the grove of the

Muses on Helicon, as well as the portraits of

Corinna at

Tanagraand of

Polybius in the cities of

Arcadia.

In general, he prefers the old to the new, the sacred to the profane; there is much more about classical than about contemporary Greek art, more about temples, altars and images of the gods, than about public buildings and statues of politicians. Some magnificent and dominating structures, such as the

Stoa of King Attalus in the

Athenian Agora (rebuilt by

Homer Thompson) or the Exedra of

Herodes Atticus at

Olympia are not even mentioned.

[6]

Pausanias'

Periegesis, unlike a

Baedeker guide, stops for a brief excursus on a point of ancient ritual or to tell an apposite myth, in a genre that would not become popular again until the early 19th century. In the topographical part of his work, Pausanias is fond of digressions on the wonders of nature, the signs that herald the approach of an earthquake, the phenomena of the tides, the ice-bound seas of the north, and the noonday sun which at the summer solstice casts no shadow at Syene (

Aswan). While he never doubts the existence of the gods and heroes, he sometimes criticizes the myths and legends relating to them. His descriptions of monuments of art are plain and unadorned. They bear the impression of reality, and their accuracy is confirmed by the extant remains. He is perfectly frank in his confessions of ignorance. When he quotes a book at second hand he takes pains to say so.

The work left faint traces in the known Greek corpus. "It was not read," Habicht relates— "there is not a single mention of the author, not a single quotation from it, not a whisper before

Stephanus Byzantius in the sixth century, and only two or three references to it throughout the Middle Ages."

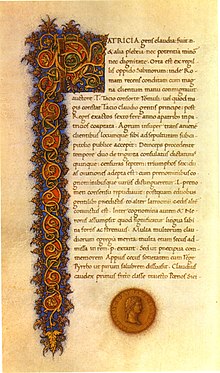

[7] We came perilously close to losing it altogether, in fact: the only manuscripts of Pausanias are three 15th-century copies, full of errors and

lacunae, which all appear to depend on a single manuscript that survived to be copied.

Niccolò Niccoli had this archetype in Florence in 1418; at his death in 1437 it went to the library of

San Marco, Florence, then disappeared after 1500.

[8] Until 20th century archaeologists found that Pausanias was a reliable guide to the sites they were excavating,

[9] Pausanias was largely dismissed by 19th- and early 20th-century classicists of a purely literary bent, who followed the authoritative

Wilamowitz in discrediting him, as a purveyor of literature quoted at second-hand, who, it was suggested, had not actually visited most of the places he described. Habicht (1985) describes an episode in which Wilamowitz was led astray by misreading Pausanias in front of an august party of travellers in 1873, and attributes to it Wilamowitz' lifelong antipathy and distrust of Pausanias. The experience of a century of archaeologists, however, has fully vindicated Pausanias.

Manichaeism (/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[1] in Modern Persian آیین مانی Āyin-e Māni; Chinese: 摩尼教; pinyin: Móní Jiào) was a major religious movement that was founded by the Iranian[2] prophet Mani (in Persian: مانی, Syriac: ܡܐܢܝ , Latin: Manichaeus or Manes; c. 216–276 AD) in the Sasanian Empire.[3][4]

Manichaeism (/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[1] in Modern Persian آیین مانی Āyin-e Māni; Chinese: 摩尼教; pinyin: Móní Jiào) was a major religious movement that was founded by the Iranian[2] prophet Mani (in Persian: مانی, Syriac: ܡܐܢܝ , Latin: Manichaeus or Manes; c. 216–276 AD) in the Sasanian Empire.[3][4]