Sigurd I Magnusson (c. 1090 – 26 March 1130), also known as Sigurd the Crusader (Old Norse: Sigurðr Jórsalafari, Norwegian: Sigurd Jorsalfar), was King of Norway from 1103 to 1130. His rule, together with his half-brother Øystein (until Øystein died in 1123), has been regarded by historians as a golden age for the medieval Kingdom of Norway. He is otherwise famous for leading the Norwegian Crusade (1107–1110), earning the eponym "the Crusader", and was the first European king to personally participate in a crusade.[1][2]

Sigurd I Magnusson (c. 1090 – 26 March 1130), also known as Sigurd the Crusader (Old Norse: Sigurðr Jórsalafari, Norwegian: Sigurd Jorsalfar), was King of Norway from 1103 to 1130. His rule, together with his half-brother Øystein (until Øystein died in 1123), has been regarded by historians as a golden age for the medieval Kingdom of Norway. He is otherwise famous for leading the Norwegian Crusade (1107–1110), earning the eponym "the Crusader", and was the first European king to personally participate in a crusade.[1][2]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The journey to Jerusalem

From Norway to England (1107-08)

Sigurd and his men sailed from

Norway in the autumn of 1107 with sixty ships and perhaps around 5,000 men.

[1] In the autumn he arrived in

England, where

Henry I was king. Sigurd and his men stayed there the entire winter, until the spring of 1108, when they again set sail westwards.

In mainland Iberia (1108-09)

After several months they came to the town of

Santiago de Compostela (

Jakobsland)

[2] in

Galicia(

Galizuland) where they were allowed by a local lord to stay for the winter. However, when the winter came there was a shortage of food, which caused the lord to refuse to sell food and goods to the Norwegians. Sigurd then gathered his army, attacked the lord's castle and

looted what they could there.

In the spring they continued along the coast of Portugal, capturing eight Saracen galleys on their way, and then conquered a castle at

Sintra (probably referring to

Colares, which is closer to the sea), after which they continued to

Lisbon, a "half Christian and half heathen" city, said to be on the dividing line between

Christian and Muslim

Iberia, where they won another battle. On their continued journey they sacked the town of Alkasse (possibly a reference to

Al Qaşr), and then, on their way into the Mediterranean, near the

Strait of Gibraltar (

Norfasund), met and defeated a Muslim squadron.

[2]

In the Balearics (1109)

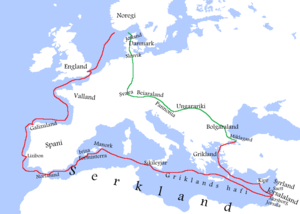

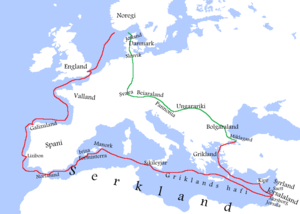

The route taken by Sigurd I to Jerusalem and Constantinople (red line) and back to Norway (green line) according to

Heimskringla. (Legend in Old Norse.)

After entering the

Mediterranean (

Griklands hafi) they sailed along the coast of the land of the

Saracens (

Serkland) to the

Balearic Islands. The Balearics were at the time perceived by Christians to be nothing more than a pirate haven and slaving center. The Norwegian raids are also the first recorded Christian attacks on the

Islamic Balearic Islands (though smaller attacks certainly had occurred).

[2]

The first place they arrived at was

Formentera, where they encountered a great number of

Blåmenn(Blue or black men) and

Serkir (Saracens)

[2] who had taken up their dwelling in a cave. The course of the fight is the most detailed of the entire crusade through written sources, and might possibly be the most notable historic event in the small island's history.

[2] After this battle, the Norwegians supposedly acquired the greatest treasures they had ever acquired. They then went on to successfully attack

Ibizaand then

Menorca. The Norwegians seem to have avoided attacking the largest of the Balearic Islands,

Majorca, most likely because it was at the time the most prosperous and well-fortified center of an independent

taifa kingdom.

[2] Tales of their success may have inspired the

Catalan–Pisan conquest of the Balearics in 1113–1115.

[2]

In Sicily (1109-10)

In the spring of 1109, they arrived at

Sicily (

Sikileyjar), where they were welcomed by the ruling

Count Roger II, who was only 12–13 years old at the time.

Kingdom of Jerusalem (1110)

In the summer of 1110, they finally arrived at the port of

Acre (

Akrsborg)

[2] (or perhaps in

Jaffa),

[1] and went to

Jerusalem (

Jorsala), where they met the ruling

crusader king Baldwin I. They were warmly welcomed, and Baldwin rode together with Sigurd to the river

Jordan, and back again to Jerusalem.

The Norwegians were given many treasures and

relics, including a splinter off the

True Cross that

Jesus had allegedly been crucified on. This was given on the condition that they would continue to promote

Christianity and bring the relic to the burial site of

St. Olaf.

Siege of Sidon (1110)

Later, Sigurd returned to his ships at

Acre, and when Baldwin was going to the Muslim town of

Sidon (

Sætt) in

Syria (

Sýrland), Sigurd and his men accompanied him in the

siege. The town was then taken and subsequently the

Lordship of Sidon was established.

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe as a Catholic ('Latin') holy war against Islam. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade (1096–1099) by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098. While it was the first Crusader state to be founded, it was also the first to fall.

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe as a Catholic ('Latin') holy war against Islam. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade (1096–1099) by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098. While it was the first Crusader state to be founded, it was also the first to fall.