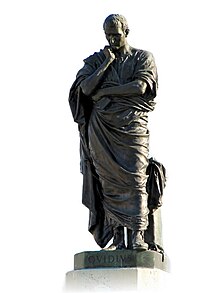

Publius Ovidius Naso (Classical Latin: [ˈpʊ.blɪ.ʊs ɔˈwɪ.dɪ.ʊs ˈnaː.soː]; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known as Ovid (/ˈɒvɪd/)[1] in the English-speaking world, was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the three canonical poets of Latin literature. The Imperial scholar Quintilian considered him the last of the Latin love elegists.[2] He enjoyed enormous popularity, but, in one of the mysteries of literary history, was sent by Augustus into exile in a remote province on the Black Sea, where he remained until his death. Ovid himself attributes his exile to carmen et error, "a poem and a mistake", but his discretion in discussing the causes has resulted in much speculation among scholars.

Publius Ovidius Naso (Classical Latin: [ˈpʊ.blɪ.ʊs ɔˈwɪ.dɪ.ʊs ˈnaː.soː]; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known as Ovid (/ˈɒvɪd/)[1] in the English-speaking world, was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the three canonical poets of Latin literature. The Imperial scholar Quintilian considered him the last of the Latin love elegists.[2] He enjoyed enormous popularity, but, in one of the mysteries of literary history, was sent by Augustus into exile in a remote province on the Black Sea, where he remained until his death. Ovid himself attributes his exile to carmen et error, "a poem and a mistake", but his discretion in discussing the causes has resulted in much speculation among scholars.

The first major Roman poet to begin his career during the reign of Augustus,[3] Ovid is today best known for the Metamorphoses, a 15-book continuous mythological narrative written in the meter of epic, and for works in elegiac couplets such as Ars Amatoria ("The Art of Love") and Fasti. His poetry was much imitated during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, and greatly influenced Western art and literature. The Metamorphoses remains one of the most important sources of classical mythology.[4]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Metamorphoses (Latin: Metamorphōseōn librī: "Books of Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem by the Roman poet Ovid, considered his magnum opus. Comprising fifteen books and over 250 myths, the poem chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar within a loose mythico-historical framework.

Although meeting the criteria for an epic, the poem defies simple genre classification by its use of varying themes and tones. Ovid took inspiration from the genre of metamorphosis poetry, and some of the Metamorphoses derives from earlier treatment of the same myths; however, he diverged significantly from all of his models.

One of the most influential works in Western culture, the Metamorphoses has inspired such authors as Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare. Numerous episodes from the poem have been depicted in acclaimed works of sculpture, painting, and music. Although interest in Ovid faded after the Renaissance, there was a resurgence of attention to his work towards the end of the 20th century. Today the Metamorphoses continues to inspire and be retold through various media. The work has been the subject of numerous translations into English, the first by William Caxton in 1480.[2]